Scientists have long believed that thawing

permafrost in Arctic soils could release huge amounts of methane, a

potent greenhouse gas. Now they are watching with increasing concern as

methane begins to bubble up from the bottom of the fast-melting Arctic

Ocean.

by susan q. stranahan30 Oct 2008: Report

For the past

15 years, scientists from Russia and other nations have ventured into

the ice-bound and little-studied Arctic Ocean above Siberia to monitor

the temperature and chemistry of the sea, including levels of methane,

a potent greenhouse gas. Their scientific cruises on the shallow

continental shelf occurred as sea ice in the Arctic Ocean was rapidly

melting and as northern Siberia was earning the distinction — along

with the North American Arctic and the western Antarctic Peninsula —of

warming faster than any place on Earth.

Until 2003, concentrations of methane had remained relatively

stable in the Arctic Ocean and the atmosphere north of Siberia. But

then they began to rise. This summer, scientists taking part in the

six-week International Siberian Shelf Study discovered numerous areas,

spread over thousands of square miles, where large quantities of

methane — a gas with 20-times the heat-trapping power of carbon dioxide

— rose from the once-frozen seabed floor.

These “methane chimneys” sometimes contained concentrations of

the gas 100 times higher than background levels and were so large that

clouds of gas bubbles were detected "rising up through the water

column," Orjan Gustafsson of the Department of Applied Environmental

Science at Stockholm University and the co-leader of the expedition,

said in an interview. There was no doubt, he said, that the methane was

coming from sub-sea permafrost, indicating that the sea bottom might be

melting and freeing up this potent greenhouse gas.

Gustafsson said he makes no claims that the methane release “is necessarily driven by global warming.”

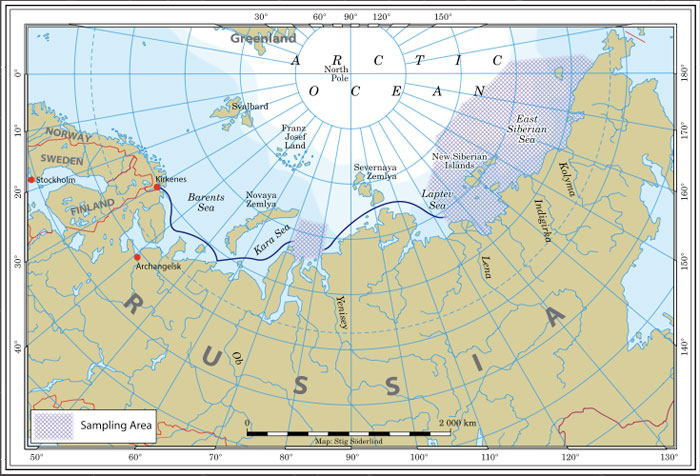

The route of the Jacob Smirnitskyi, a

Russian research vessel that traveled along the Russian Arctic coast

this summer as part of the International Siberian Shelf Study.

Scientists detected extremely high levels of methane in the sea during

the six-week voyage. The purple grid shows areas where researchers

sampled gases.

But a growing body of data showing that more methane is emanating from

the rapidly thawing Arctic Ocean has caught the attention of many

climate scientists. Could this be the beginning, they wonder, of the

release of vast quantities of sub-sea Arctic methane long trapped by a

permafrost layer that is starting to thaw?

In recent years, climate scientists have been concerned about

a so-called “methane time bomb” on land, which would be detonated when

warming Arctic temperatures melt permafrost and cause frozen vegetation

in peat bogs and other areas to decay, releasing methane and carbon

dioxide. Now come fears of a methane time bomb, part two, this one

bursting from the sea floor of the shallow Arctic continental shelf.

The Arctic sea floor contains a rich, decayed layer of vegetation from

earlier eras when the continental shelf was not underwater.

So little data is available from the Arctic Ocean that no

scientists dare say with certainty whether the world is watching the

fuse being lit on a marine methane time bomb. But researchers such as

Natalia Shakhova —a visiting scientist at the University of Alaska in

Fairbanks and a participant in some of the Siberian Shelf scientific

cruises — are concerned that the undersea permafrost layer has become

unstable and is leaking methane long locked in ice crystals, known as

methane hydrates.

"Now come fears of a methane time bomb, part two, this one bursting from the sea floor of the shallow Arctic continental shelf."One thing is certain: the shallow Siberian Shelf alone covers

more than 1.5 million square kilometers (580,000 square miles), an area

larger than France, Germany, and Spain combined. Should its permafrost layer thaw,

an amount of methane equal to 12 times the current level in the

atmosphere could be released, according to Shakhova. Such a release

would cause “catastrophic global warming,” she recently wrote in

Geophysical Research Abstracts. Among the many unanswered questions is

how quickly — over years? centuries? — methane releases might occur.

Said Gustafsson, “The conventional view is that the permafrost

is holding these large methane reservoirs in place. That is a view that

we need to rethink and revise.”

What concerns some scientists is evidence from past geological

eras that sudden releases of methane have triggered runaway cycles of

climate upheaval. Martin Kennedy, a geologist at the University of

California at Riverside and lead author of a paper published in Nature

in June, speaks in near-doomsday terms, warning that rising methane

emissions — from land and sea — threaten to radically destabilize the

climate. Ice core studies in Greenland and Antarctica have shown that

Earth’s climate can change abruptly, more like flipping a switch than

slowly turning a dial.

“I’m very concerned that we’re near the threshold and we’re

going to see the tipping point in 20 years,” Kennedy warns. Temperature

increases in the Arctic of a just few degrees could unleash the huge

storehouse of methane, which some have estimated would be comparable to

burning all recoverable stocks of coal, oil, and natural gas.

"What

concerns some scientists is evidence from past geological eras that

sudden releases of methane have triggered runaway cycles of climate

upheaval."Kennedy’s Nature article bases his warnings on a long-ago event. Sediment samples gathered in south Australia led Kennedy’s team to theorize that a catastrophic era of

global warming was triggered some 635 million years ago by a gradual —

and then abrupt — release of methane from frozen soils, bringing an end

to “Snowball Earth,” when the entire planet was encrusted in ice. He

sees similarities in the mounting threats of thawing terrestrial and

marine permafrost today. The question, he asks, is what will set the

process in motion and when.

“Do we have a substantial risk of crossing one of these

thresholds?” he asked in an interview. “I would say yes. I have

absolutely no doubt that at the current rate of [greenhouse gas

emissions] we can cross a tipping point, and when that occurs it’s too

late to do anything about it.”

As with much climate research, the science is complex and

opinions can vary dramatically. David Lawrence of the National Center

for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado, is concerned, but not

alarmed. Lawrence was lead author of a paper in Geophysical Research

Letters, also published in June, that documented the consequences of

the record loss of Arctic sea ice in 2007. Based on climate models,

Lawrence and his team theorized that during periods of rapid sea-ice

loss, temperatures could increase as far as 900 miles inland,

accelerating the rate of terrestrial permafrost thaw. From August to

October of 2007, they reported, temperatures over land in the western

Arctic rose more than 4° F above the 1978-2006 average.

“If you give it [the land] a pulse of warming like that it

could lead to increased degradation of permafrost,” Lawrence said in an

interview. “It’s not quite a runaway situation, but it does accelerate

once it starts to thaw and accumulates heat.”

Arctic soils hold nearly one-third of the world’s supply of

carbon, remnants of an era when even the northern latitudes were

covered with lush foliage and mammoths ranged over grassy steppes.

Scientists estimate that the Siberian tundra contains as much buried

organic matter as the world’s tropical rain forests.

Disappearing Arctic sea ice — summer ice extent was at its

lowest level in recorded history in 2007 and almost hit that level in

2008 — also will warm the Arctic Ocean, since a dark, ice-free sea

absorbs more solar radiation than a white, ice-covered one. In

addition, warmer waters are pouring in from rivers in rapidly warming

land regions of Alaska, Canada, and Russia, also increasing sea

temperatures.

"Scientists are stepping up their monitoring of the land and the sea in the Arctic."Rising ocean and air temperatures mean not only the continuing

disappearance of Arctic sea ice — many scientists now think the Arctic

Ocean could be ice-free in summer within two decades — but

also mean that permafrost on the sea floor could thaw more quickly.

Scientists are unsure how rapidly the subsurface permafrost is thawing,

or the exact causes. One possible cause could be geothermal heat

seeping through fault zones. In any case, scientists agree that Arctic

sub-sea permafrost — with a temperature of 29° F to 30° F— is closer to

thawing than terrestrial permafrost, whose temperature can drop as low

as 9.5° F.

At this point, scientists are stepping up their monitoring of

the land and the sea in the Arctic, watching to see if either time bomb

— terrestrial or marine — is showing signs of going off. So far, data

are scarce and monitoring networks don’t exist. “That makes it very

difficult to understand and evaluate the future,” Lawrence said.

Although scientists know that methane has been released in the region’s

water for eons, they are unsure if the new findings represent a

short-term spike or long-term trend.

Pending more research, Orjan Gustafsson shares Lawrence’s

caution. When he was asked how close Earth may be to a tipping point of

irreversible climate change, he replied: “Everyone would like to know

the answer to that. I don’t think anyone can say.”

the article is reprinted from Yale Environment 360

e360.yale.edu